Announcing: Designing the American Century: The Public Landscapes of Clarke and Rapuano, 1915–1965 by Professor of City and Regional Planning Thomas J. Campanella

Campanella's most recent book was released after he began research decades ago as a Cornell student on two largely underrecognized landscape architects who deeply shaped the urban geography of the New York City we know today.

According to Professor of City and Regional Planning Thomas J. Campanella's latest book, Designing the American Century: The Public Landscapes of Clarke and Rapuano, 1915–1965 (Princeton University Press, 2025), Gilmore D. Clarke and Michael Rapuano were the foremost spatial designers of the American Century. Yet their vast portfolio of public works and landscapes has been largely overlooked by both journalists and fellow scholars of the built environment. Campanella's research reveals how Clarke and Rapuano's parks and parkways, highways, housing, and urban renewal projects helped modernize — for better or worse — the New York City metropolitan region, while creating some of its most iconic and enduring landscapes.

Campanella shares what spurred his ongoing research and fascination, as well as some personal realizations he has made since beginning the project over thirty years ago as a student at Cornell.

Edith Fikes: In talking about this book, you describe landscape architects Gilmore D. Clarke and Michael Rapuano as "unsung giants of the American Century." Let's unpack some of this.

Who were Gilmore D. Clarke and Michael Rapuano?

Thomas J. Campanella: Clarke and Rapuano were both Cornellians, and they both trained in landscape architecture, though in Clarke's time, landscape architecture at Cornell was somewhat charmingly known as "rural art." By the time Rapuano was a student in the 1920s, the program had moved from what today is CALS to the College of Architecture, now AAP. Rapuano went on to win the 1927 Rome Prize in Landscape Architecture. He was a star student at both Cornell and the American Academy in Rome, so Clarke heard about Rapuano and hired him immediately after he returned home in 1930. They worked together for several years in Westchester County, creating the first regional park system of the motor age. The parkways they designed provided the template for highways all over the world. With the coming of the Great Depression and all the New Deal public works underway in New York City (and the rest of the country), Clarke and Rapuano established a practice that quickly expanded to include urban design, civil engineering, and urban planning.

Incidentally, Clarke was also the first professor of City and Regional Planning at Cornell and later served as dean of the College of Architecture for many years. He effectively established the department where I teach today. He would commute from New York City twice a week on an overnight train called the Black Diamond — a luxury we no longer have.

Henry Hudson Parkway and Riverside Park looking south toward the 79th Street roundabout, November 1937. photo / Fairchild Aerial Surveys, Inc., Gilmore D. Clarke Papers (15-1-808), Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University

You really can't throw a stone in New York today without hitting something Clarke and Rapuano created, right down to the city's most ubiquitous park bench model. — Professor of City and Regional Planning Thomas J. Campanella

EF: What do you mean when you say Clarke and Rapuano were "giants," and why would their work be overlooked if they made such a lasting impact?

TC: Clarke and Rapuano helped create some of the most iconic public landscapes of mid-century New York City — Bryant Park, Cadman Plaza Park, the Brooklyn Heights Promenade, and Jacob Riis and Flushing Meadows parks in Queens. The site plans for both the 1939 and 1964 World's Fairs, the first plan for what today is JFK Airport, and even the UN Headquarters in Manhattan — all their work. You really can't throw a stone in New York today without hitting something Clarke and Rapuano created, right down to the city's most ubiquitous park bench model. And their impact extended far beyond New York. They designed parkways in Philadelphia and Washington, DC, and made urban renewal plans for Portland, Nashville, and Cleveland. Clarke personally chose the site for the Pentagon.

There are a couple of reasons why their contributions have been overlooked. Because these were enormous public projects requiring huge teams of people, discerning the precise role of the various parties involved has proven difficult for journalists and scholars. It is much easier to simply attribute all creative authorship for, say, a project like Riverside Park or the Henry Hudson Parkway, to the administrator at the top. In New York, it was often Robert Moses. Moses was a brilliant — if ultimately misguided — executive and smart enough to surround himself with gifted architects and engineers. But he was not himself a designer.

EF: What inspired your research into their story and contribution?

TC: Well, 35 years ago, I began this project as my master's thesis at Cornell. I studied under Emeritus Professor Lenny Mirin, who, like me, is from Brooklyn. In the 1970s, he once took a class to visit Clarke and Rapuano's office. From Lenny, I realized that these two men shaped the New York I grew up in. I was astonished that no one had written about them. I mean, they were the Olmsteds of the 20th century! Here was this huge, glaring hole in the historiography of American urbanism. My book isn't the last word on the subject, but I like to think the hole has been plugged for now.

Bryant Park looking south toward Lowell Fountain, 1936, with scrolled hedges, now long gone, that were a Betty Sprout signature. image / Clarke & Rapuano Landscape Architecture Collection, New York Historical Society

EF: What surprises, if any, came up for you while researching and writing this book?

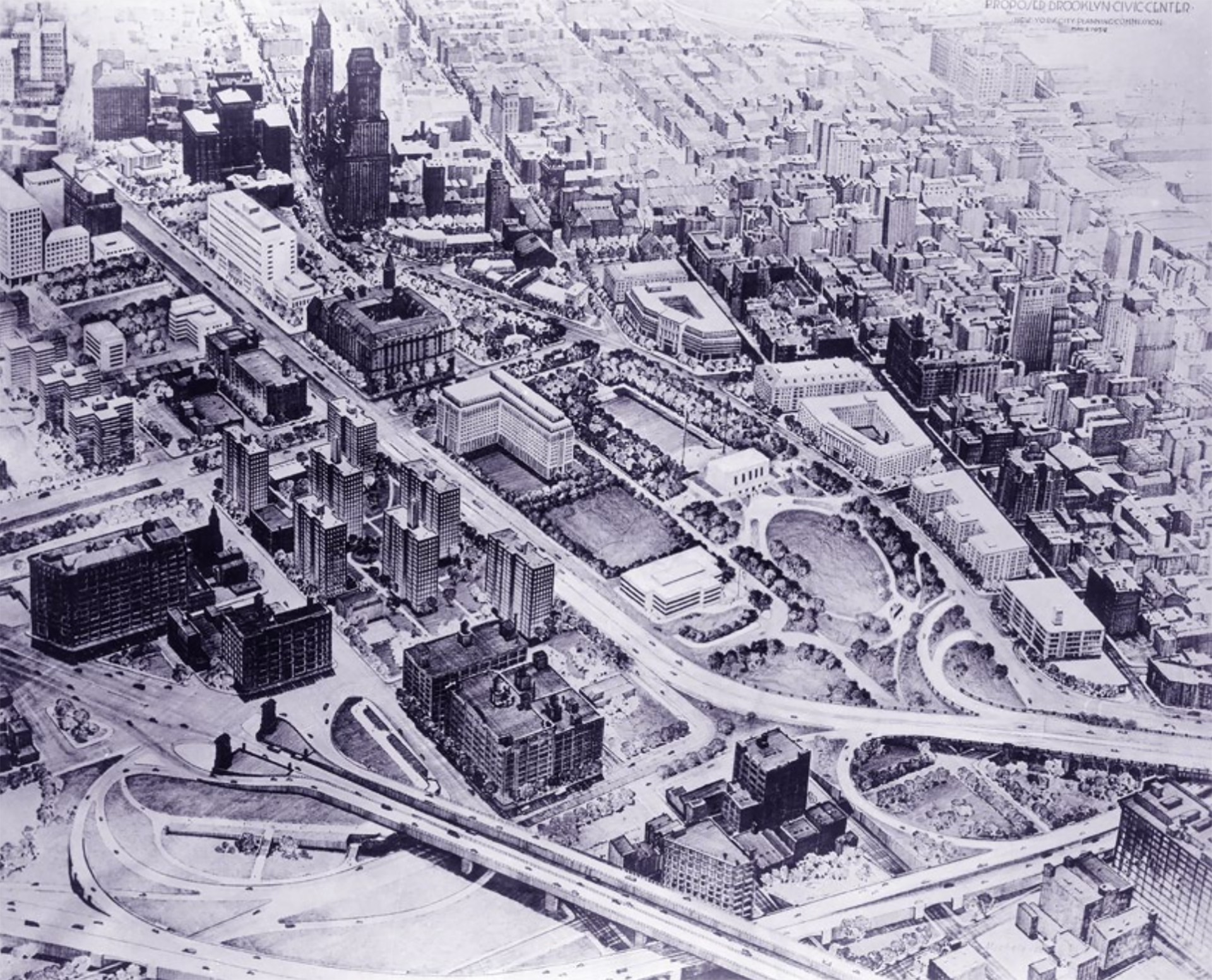

TC: One big surprise was how closely some of the more negative impacts of Clarke and Rapuano's projects affected my family. For example, my mother grew up in an impoverished neighborhood by the Brooklyn Navy Yard, which is now called Vinegar Hill. By the 1950s, one of Moses's huge urban renewal projects, the Brooklyn Civic Center, had leveled her neighborhood and effectively destroyed her childhood world. I discovered that Clarke and Rapuano were the project's master planners. Certainly not everything Clarke and Rapuano did was great. Millions of people still enjoy their parks and parkways, but they were also involved with some of the era's most egregious urban renewal projects.

Aerial perspective of Brooklyn Civic Center and Cadman Plaza, 1952, Julian Edward Michele, delineator. image / New York City Department of Parks and Recreation

EF: What gap does your book fill in the history and narrative of New York City and Western Modernism?

TC: For one, it helps counter the "Great Man" narrative about Robert Moses, generated by Robert Caro's 1974 biography, The Power Broker. It also sheds light on the heroic New Deal era, when American landscape architects resuscitated their profession's founding commitment to public parks and public works. Before my book, there was only one small published study on this vast subject. I also hope my book generates fresh appreciation for the immense impact that some of our alumni have had on the world we know today. Even here at AAP, the names Clarke and Rapuano are all but forgotten, yet these men and their works have touched the lives of millions.