Announcing: Architecture and the Right to Heal, Resettler Nationalism in the Aftermath of Conflict and Disaster

Cornell AAP Architecture Professor Esra Akcan released a new book this fall examining architecture's dual role as both a cause of human casualties and an agent for the public good with the potential to ameliorate traumas following conflict and crises.

In Architecture and the Right to Heal (Duke University Press) architect and historian Esra Akcan highlights the ongoing struggle to heal after conflicts and disasters in formerly Ottoman-held lands, ranging from enforced disappearance to mass extinction. Putting forth the concept of resettler nationalism as a source of displacement and partition, Akcan argues that while architecture and urban planning have historically contributed to segregation and subjugation, as future-looking practices, they could instead confront painful pasts and promote more just spaces that address intersecting social, global, and environmental issues.

Upon the release of her latest title, Akcan shares thoughts on her process and intent.

What initially inspired Architecture and the Right to Heal? How did the context in which you wrote it shape your approach to research and writing?

While I could not have predicted them when I started my research, a pandemic, an earthquake, three wars, possibly two genocides, famines, several floods, and almost weekly climate disasters have occurred on the land I cover in this book while I was working on it. I began by writing the first chapter on the Saturday Mothers, a group in Istanbul that protests enforced disappearances, partly as a result of my personal life experience and the immediate events that unfolded after I signed a peace petition. I was also exasperated by the turn of events in the US and inspired by resistance and protests on our campus, but I think conflicts and disasters of this kind constitute a globally shared context, rather than my own small setting. So, I continued, convinced that we as architects, historians, and other professionals cannot remain bystanders.

The Argos Hotel in Uçhisar, Cappadocia, Turkey, designed by Aslı Özbay et al. (1996–2017), features a subterranean space that has been retrofitted as a museum. photo / Galip Hasan Temur

In your book, you write: "To insist on imagining the future is sometimes the only resistance against the destructive powers in times of crisis." Can you explain what you see as architecture's role in imagining futures that might reverse damages after conflict and disaster?

When a crisis is so intense that it makes us feel helpless, I find myself doing two things: imagining a future where the crisis is already resolved and asking how we got here. Architecture and planning are rooted in futurity and are critical to post-conflict and post-disaster recovery, but they also have a history of creating unjust and disaster-prone spaces. I wanted to tackle the wounds we live with by explaining how architecture has been party to political and ecological harm, and to foreground the history of architects who have worked toward healing.

The book's forward momentum comes from chapters proceeding from individual to communal and to planetary healing. Each type of conflict and disaster is discussed as it relates to specific architectural programs. For example, housing is implicated in healing after mass displacement and earthquakes; memorials matter for repairing state violence; master plans and campuses are implicated in climate disasters; and gardens, parks, and ruderal landscapes are critical to preventing the loss of biodiversity.

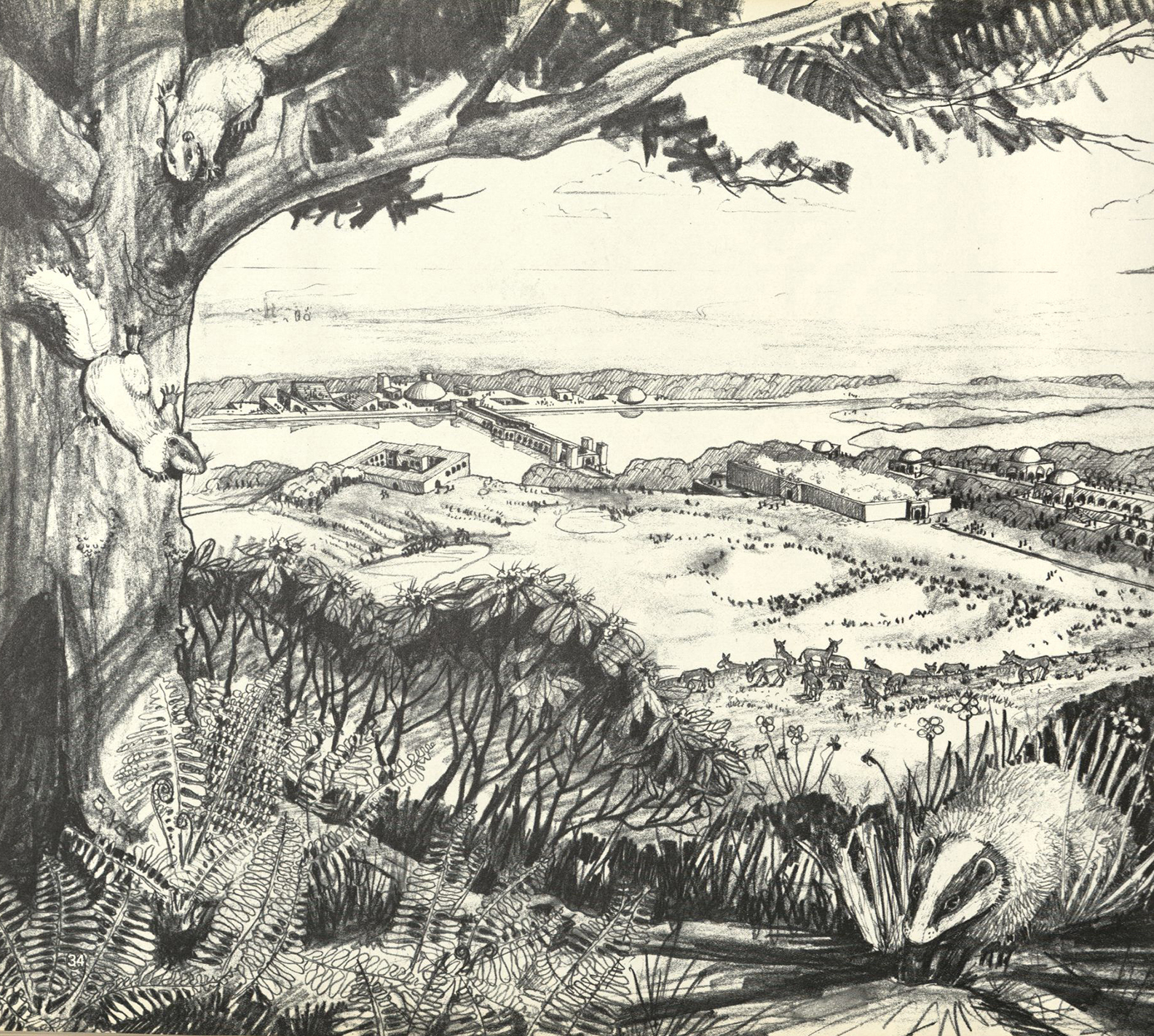

A perspective drawing of Pardisan Park, an environmental park in Tehran, Iran, designed by WMRT, Ian McHarg, Nader Ardalan, and Laleh Bakhtiyar in Tehran and Philadelphia (1974–80). image / Nader Ardalan (provided)

You open by saying that your focus is specifically not about post-war reconstruction. What is the difference between post-war conditions and the conflicts and disasters you focus on?

Rather than war damage induced by a party considered external at a given moment, I look at what might be called internal violence: social-, state- or business-led aggressions induced by leaders or institutions that are meant to protect their subjects. The book starts with enforced disappearance and ends with extinction. It moves from the suspicious vanishing of individual human beings to entire species. The chapters between give a name to ongoing injuries: partition, collapse, and climate disaster.

I have found that internal violence is more common than external, and despite ample scholarship on postwar reconstruction, healing from these traumas is unexplored. In addition to books on postwar reconstruction, numerous journalistic essays report on state violence and climate change. My book demonstrates that these issues can be addressed in a more extensive and layered way through architectural history. One difference between postwar reconstruction and healing after internal violence, for instance, is the status of received knowledge and established history. When perpetrators win or remain in power after a violent act, as is often the case for internal violence, the historian's task is harder. We must find and demonstrate the truth to counter official histories that hide facts and even produce false ones that support denial. A poignant example is the difference between genocide accountability and denial in contexts where the perpetrators lost, as opposed to cases when they have become nation-builders.

Haj Al-Safi House in Khartoum North, Sudan, by Abdel Moneim Mustafa (1967–69). photo / Esra Akcan

What changes in architecture and planning practices does this book call for?

First, I should qualify what calling for entails, because the difference between positioned history and what Manfredo Tafuri criticized as operative history is often overlooked. The latter instrumentalizes architectural history in the service of specific architects and architectural movements, thereby betraying the epistemological grounding of history. As a scholar, my primary loyalty is to knowledge, to finding the truth about the past, and establishing what I think is the most truthful and fair-minded position in uncovering this history, rather than determining, or worse, promoting action plans or stylistic preferences of a select group of architects.

Architecture and the Right to Heal locates spaces of political and ecological harm, and makes a call to think about healing by confronting violence and violations, and instituting accountability and reparations. These include advocating for climate reparations to global victims of first-industrializing countries, implementing transitional justice measures, revealing disappeared urban layers, retrofitting buildings with erased memories, being a connector rather than a divider, and so on. The book introduces discussions from other disciplines such as transitional justice and new conventions in human rights, energy transition and carbonization history, and more-than-human epistemology. It demonstrates the need for thinking and acting for social, global, and environmental justice together. Beyond this, I prefer that architects and planners as readers, make their own decisions about how exactly they can contribute to this call.

Of course, I have my own concrete suggestions as a reader and architect myself, but this is not the goal. During my research, I was triggered by countless examples where architecture was complicit in the conflicts and disasters from which I had to choose to write about, but it was very difficult to find examples where architects were part of meaningful healing. One of my calls to architects, planners, and readers is perhaps an invitation to think about this.